Passkeys beat passwords.

Not everyone agrees. But I’ve found that some dissent is rooted in a lack of understanding how passkeys work.

I don’t blame the skeptics. Passkeys are simple to use, but their technical nuances can be a headache to understand. So let’s get into the details.

What a passkey is

Passkeys are the informal name for the WebAuthn standard for authentication. It relies on asymmetrical encryption (aka public-key cryptography). When you create a passkey, a public-private key pair is generated. The website gets the public key. You own the private key, which remains secret. It facilitates the authentication process, but it’s never directly shared for the verification process to complete. Nor can it be extrapolated from the public key.

Your private key is tied to wherever you save it, with two main options for storage:

Cloud storage

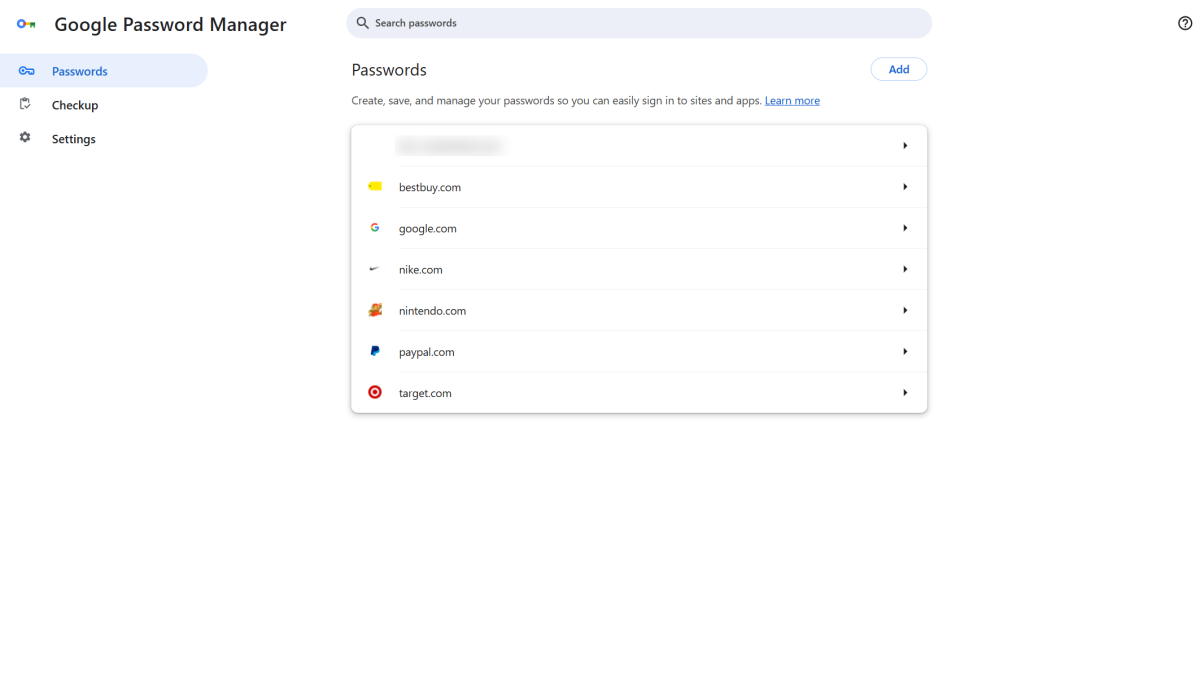

Apple, Microsoft, and Google all can store both passwords and passkeys to your account.

PCWorld

Saving your half of a passkey to a cloud-based service offers the most flexibility—you can access it from any of your devices.

For many people, this method will happen through a Microsoft (Windows), Apple, or Google account. You can also opt to save to most third-party password managers now, too.

Currently, you can’t freely transfer passkeys between cloud services, but that should change in the coming months. Apple just enabled porting (aka CXP) in iOS 26 and macOS 26, as has third-party password manager Bitwarden, which allows for secure import and export of both passkeys and passwords with other compatible services.

The main advantage of cloud storage is convenience—again, as long as you can access your account, you can use passkeys saved to it. But the disadvantage is that if anyone breaks into your account, they can use those passkeys, too.

Local storage

YubiKey

When passkeys first launched, these were saved locally to your phone or PC. You could also save them to a security key like a YubiKey or Google Titan Security Key.

Nowadays, most passkeys saved to a phone or PC will get linked to whatever cloud account you’re signed into. If you want to save a passkey to a piece of hardware that you have complete control over, you’ll have to use a local-only password manager (like KeePassXC) for your PC or a security key.

The advantage of local storage is that a bad actor needs access to the hardware to get at your passkeys. On the flip side, the disadvantage is that if you lose the device and have no other passkeys or alternative methods for login, you can’t get into your accounts.

Roaming vs Platform Authenticators

I’ve defined the ways you can store a passkey in practical terms above—but be aware that the WebAuthn standard defines it differently. It distinguishes between “roaming” and “platform” authenticators. A security key (e.g., YubiKey) is an example of a roaming authenticator; you can move it between different devices. Devices like PCs and phones are considered “platform” authenticators—you won’t be shifting the passkey between devices for use.

What a passkey is not

Not limited in use

PCWorld

Passkeys get tied to the service or device they’re created on—which has led some people to believe that they’re bound to ecosystems. (That is, Google, Apple, Microsoft, and third-party password managers all want to lock you into their service, since you can’t yet freely move the passkeys between them.)

But passkeys differ from passwords—you can create multiple passkeys for a single site (versus only ever having a lone password). Think of it as similar to a housekey. Each key for a particular lock can only exist in one place at a time (this is why we can’t ever find them when we need them…). But you can have more than one key to open that lock. The difference between a housekey and a passkey is that extra housekeys are copies. Extra passkeys are unique and can’t be copied to be used elsewhere, so they’re still secure.

So you could create a passkey for a particular site for your Microsoft account, another for your Apple account, and yet a third for your Google account, and all would work for logging in. You’re not truly trapped into any one of those ecosystems.

Not forever bound to a device or service

Apple

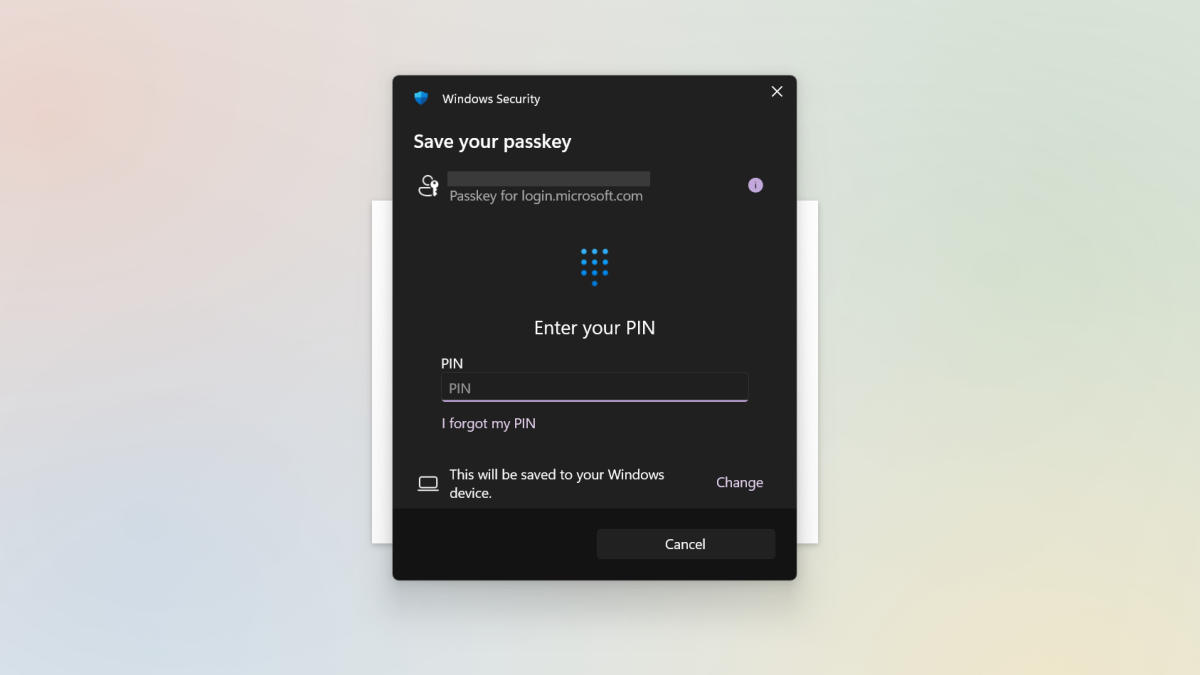

At launch, passkeys were specifically tied to whatever device or service they were created for, which is why the ability to create multiple was so vital in making them usable.

In some ways, this was a security feature—if you had a passkey that could never be moved, then you also never had to worry about anyone being able to transfer that private key away from you. (At least, short of this XKCD method.)

That, however, only applied to locally saved passkeys. If you had a passkey stored in the cloud, you still had to be careful that no one gained unauthorized access to the account it was saved to.

It also however was a pain in the butt for many people—if a device with your passkeys became lost, stolen, or damaged, you were out of luck if you didn’t have any backup passkeys or alternative login methods set up.

So now, the ability to securely transfer your passkeys is rolling out.

Passkey vulnerabilities

Now let’s talk about vulnerabilities—and sort out some of the confusion I’ve heard people express about how passkeys stack up against passwords. In all of these scenarios, we’re assuming implementation is done correctly.

Phishing

Phishing can be defined as an attempt to trick people into sharing sensitive information. It’s a broad umbrella term and comes in different flavors, like social engineering and malware.

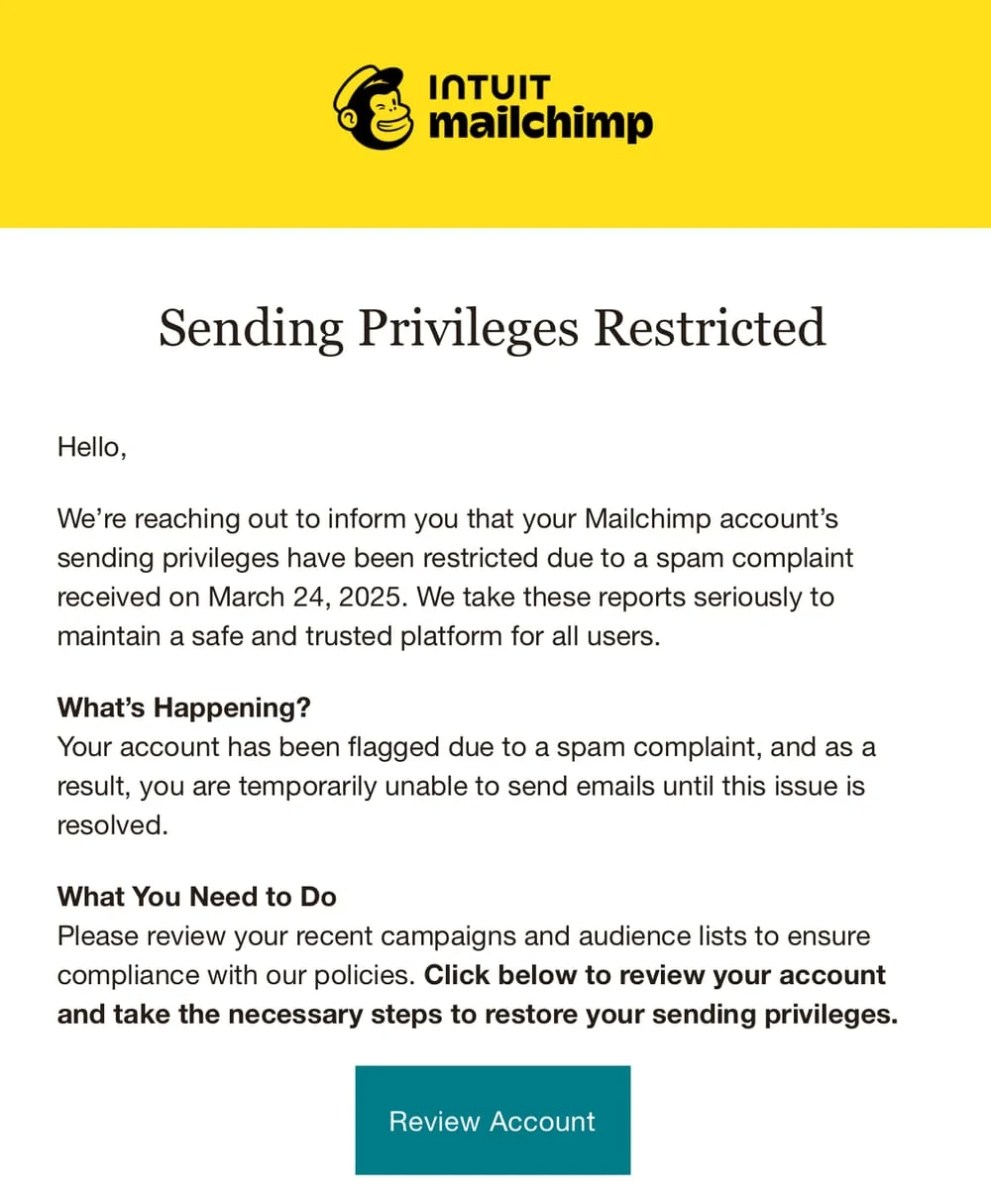

Simple phishing attacks simply ask for your credentials via emails, text messages, or calls from bad actors posing as legitimate businesses. More sophisticated ploys lure victims to fake websites masquerading as legitimate. When login info is input, the user ID and password get stolen. Even accounts with two-factor authentication aren’t always safe—that info can be grabbed in real time, too.

Troy Hunt / HaveIBeenPwned

Experts say passkeys are phishing resistant for two main reasons. The first, an attacker can’t actually steal elements that make up the passkey. The public key is indeed public by design, and the private key is kept only by you. They work together to create the piece of shared data that completes the authentication process, but they aren’t what’s exchanged. So nothing can be stolen (or used) in the same way as a user ID and password.

Second, the standard also only allows use of a passkey with the originating domain. If a phony website attempts to trick you into using a passkey for authentication, your browser will check for the original domain linked to the passkey and shut down the attempt. The phishing domain won’t match. You won’t be able to override this process as you can with password autofill, either. The authentication process just won’t begin, and you can’t force it.

Similarly, if an attacker places a legitimate login form within an iframe, it shouldn’t work. For authentication to work when an iframe is in use, the handoff requires established coordination between the domains in order to accept the mismatch. While not impossible, a fake phishing site likely cannot enact this implementation between its phony domain and the official one.

Note: This information is current to now—attackers are always coming up with new ways to find a way around roadblocks such as these. The landscape could change with time.

Meddler in the middle (MitM) attacks

In a MitM attack, hackers literally position themselves between you and the site you’re communicating with, so that the data passes through them. So in one variation of this attack, bad actors will steal your credentials while feeding them to the legitimate site—including two-factor authentication codes. Afterward, the attacker has a viable session active, and no longer needs 2FA to begin account takeover.

Passkeys protect against this kind of credential theft, but not a variant known as session hijacking. More traditionally, session hijacking focuses more on the idea of cookie theft, so that an attacker can place the cookies on their own device and then access the account through the validated session.

Justin Morgan / Unsplash

Passkeys can’t protect against this—which is why preventing malware on your system is crucial. Website operators can mitigate this kind of attack through things like tying the session to the device or locale, etc. But that’s out of the passkey’s realm of influence. Once the authentication happens, its job is over.

In theory, malware on your system could also mess with or tamper with your browser’s ability to execute the WebAuthn standard as designed to, so again, still best to be careful about what you install. But this is not a knock on passkeys—malware can just as easily steal your passwords directly from your password manager, too.

One last passkey consideration

Overall, a passkey is more secure than a password—and more convenient than using a password plus two-factor authentication.

But how you secure your passkeys could matter, if you have reason to think that your biometric data isn’t protected. For online security purposes, your fingerprint or face will be more secure than a PIN, which can be shared more easily and widely. But within some jurisdictions (like the United States), you can’t be compelled to reveal a PIN to the government. Biometrics aren’t protected in the same way.

For most people, such a distinction won’t be a concern. But for those who have to weigh such matters, it’s worth knowing.